This is the exceptional collection in all America, and it is being neglected. I urge you to make the reinstallation of Islam your highest priority. If you were to create an Islamic wing, you’d find that our holdings – splendid bronzes, excellent silver, majestic tiles, gorgeous carpets, intricate woodcarving, masterful pottery, and glorious miniatures – would become as popular as the European paintings. You laugh? [1]

These words were recollected by the influential former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) Thomas Hoving in his memoir Making the Mummies Dance, remembering an exchange with Maurice Sven Dimand, curator at the Met, in 1967. This was no laughing matter, and in fact, the museum created the Department of Islamic Art eight years later, which became one of the most important exhibition spaces on the subject. In 2003, almost three decades later, the galleries were closed for renovation; the public came face to face with them once again on November 1, 2011.

Since the decision was made to expand the department dedicated to Islamic arts, the museum – which ideally ought to be a safe haven from geopolitics – found itself dealing with a loaded subject matter; although the September 11, 2001 attacks have encouraged cultural institutions to show a different side of Islam, other factors such as the U.S. military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan and more recently, the Arab Spring, were perhaps unforeseen. The start of the renovation of the department, following the events of 2001 by only two years, cannot be analyzed away from cultural diplomacy, and evidently, politics.

This article will survey the representation of Islamic art in the Met, and will be followed by two other analyses; that of the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo and the Louvre Museum in Paris. In the space of a year, these three museums overhauled their Islamic art collections and, although the timeline is similar, each museum has a distinct agenda influencing its curatorial decisions.

As with all collections, it is somewhat challenging to determine a title that will encompass the artifacts. The Department of Islamic Art at the Met was not spared. Although the department has retained the same name, the galleries themselves have been relabeled the Galleries of Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia and Later South Asia, also known as ALTICALSA. The same galleries were unambiguously denominated the “Islamic Art” galleries until they were closed in 2003. Their recent murky designation seems so lengthy that few people would actually remember it. Although the galleries are still commonly identified as “the galleries of Islamic art”, according to the department’s published catalogue, Masterpieces from the Department of Islamic Art, the expression “Islamic art” is not appropriate for this specific collection, as the Islamic world covers more territories than those shown in the collection. Contrary to this assertion, however, a map affixed at the entrance of the exhibition area is entitled “The Islamic World,” and delineates North and Central Africa, Europe and Asia. The cities that the Met considers as part of the Islamic world are inscribed; nevertheless, demarcation lines and dates are lacking from the map. It is unclear what constitutes this “Islamic world” and the reality of this territory covered in the exhibits becomes blurry. In fact, those terms are restructured to fit the needs of the museum.

The “Islamic world” remains an undefined setting. This new nomenclature preferred by the Met suggests new political and geographical categories, which might not only change the interpretation of what constitutes Islamic art, but also what Islam really is. The coalescing of different lands, countries and nations under a single appellation, such as “Arab Lands” or “South Asia,” puts those lands, countries and nations under only one category, where all of them would be considered equal. Equality, naturally, is an ideal paradigm, but does it really suit this specific context or even the reality of the region?

.jpg) [Gallery 464 Later South Asia (16th-20th centuries). New Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia. Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.]

[Gallery 464 Later South Asia (16th-20th centuries). New Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia. Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.]

By using such general terms, the museum is reconstructing those categories to fit a chosen cultural landscape. None of the categories in the gallery names are precise or refer to a specific area or country. The Met has also launched a website in the form of a blog to discuss the “Renovated Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia and Later South Asia.” It is accessible through the museum’s main website, and is available in English, Arabic, Turkish, Persian, Russian and French. The language used is similar to that used in all the marketing material for the department. Sheila Canby, head curator of the Department of Islamic Art, observes:

Because the objects in our galleries are primarily secular in nature, they can easily be appreciated both for their innate utility and for their astonishing beauty, whatever the viewer’s background may be. [2]

It is true that Islamic art is not art only found in religious spaces, but Canby’s statement is erroneous, and does not reflect the reality that the cultural and religious elements of Islamic art are interwoven. Highlights of the collection include Qur’an manuscripts from Syria, Turkey, Iraq and Tunisia and an Iranian mihrab, which is in fact only present in religious architecture. By defining the objects as “primarily secular in nature,” the curator is once again distancing the entire collection from a religion it is so closely tied to. The fact that she needs to clarify if it is or is not associated to a faith shows that there is indeed a determination to prove that each is dissociated from the other.

[Folio from the Blue Qur`an (ca. 9th-10th centuries), probably from Tunisia. Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

[Folio from the Blue Qur`an (ca. 9th-10th centuries), probably from Tunisia. Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

It is also worth mentioning that the title of the galleries in other languages translates the phrase “Arab lands” to “Arab countries,” which then has a very different meaning (for example, Spain was an Arab land; it is nonetheless not an Arab country).

This belabored secular presentation is utterly distinctive from what was previously depicted. In the 1987 book The Islamic World by Stuart Cary Welch, special consultant in charge at the Department of Islamic Art, the title is mentioned in the introductory writings, followed by:

Verily God is beautiful and loves beauty.

- Saying of the Prophet Muhammad. [3]

Later in the text, Welch writes that the “seeds of Islamic art are found in the life and teachings of Muhammad the Prophet, a historical personage very much of his time and place”. The Prophet is also described as “this extraordinary mystic and visionary”. Such expressions are not used today, as they associate Islamic art to the religion of Islam. The current representation of Islamic art is done in a way that is non-religious and there is an implicit effort to dissociate the art from this religion in order to open the discussion, and make Islamic art more accessible and especially less unnerving in light of the Islamophobia that still grips American political discourse.

If we go further back in the history of the museum and review publications from the 1930s, Dimand uses expressions from “A Handbook of Mohammedan Decorative Arts” [4] such as “proclaiming aggressive war on all unbelievers” and “preparing the conquest of the world”. By giving this complementary dimension to these traditions, cultures and arts, the subject matter acquires more depth and a more global image can be made. Those expressions would not be used in a similar context today, due to the sensitive nature of the topic. It is obvious that back then, curators at the museum strongly associated Islamic art to the religion of Islam.

Along with the change in name and presentation of the department, the renovation gave birth to new, additional galleries. The initial twelve galleries dedicated to Islamic art that were established at the New York museum in 1975 were much smaller than the present fifteen. Back then, the introductory gallery gave way to the Nishapur Excavations on the right, which exhibited artifacts and architectural elements dating from the 9th to the early 12th century that were discovered by the museum in digs conducted between 1935 and 1947, to the art of the “Early Centuries” straight ahead, or to what is now called the Damascus Room (previously called the “Nur ad-Din Room of 1707 from Damascus”) on the left. Although the architectural skeleton is similar, overall the 1975 space was noticeably smaller.

.jpg) [Reception Room (Qa`a), dated 1707, from Damascus, Syria. Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

[Reception Room (Qa`a), dated 1707, from Damascus, Syria. Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

In May 2003, as part of the “21st-Century Met” project, the interior of the south wing of the museum’s Fifth Avenue building underwent a USD 40 million renovation. The galleries dedicated to Islamic art were closed in order to build Greek and Roman galleries beneath them. The present exhibition includes more architectural elements, such as the Moroccan Court, a late-mediaeval inspired Andalusia reproduction of a courtyard. The Damascus Room is designed as a formal Ottoman space. The composition is fashioned in an original manner, with inlaid marble, carved, painted designs and a fountain, all evincing a mixture of Turkish, Arab, early Mamluk and European styles.

[Gallery 456: Moroccan Court. New Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia. IMage copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

[Gallery 456: Moroccan Court. New Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia. IMage copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

One can also notice that the display of the galleries was and still is divided chronologically, as well as geographically. The only contrast is that in 1975, one gallery (4c) was dedicated to The Art of the Mosque. This gallery showcased various elements from mosque settings. Its absence reinforces the new frame of mind that for the inaugurated galleries to represent Islamic art, including religious objects, they must be as secular as possible.

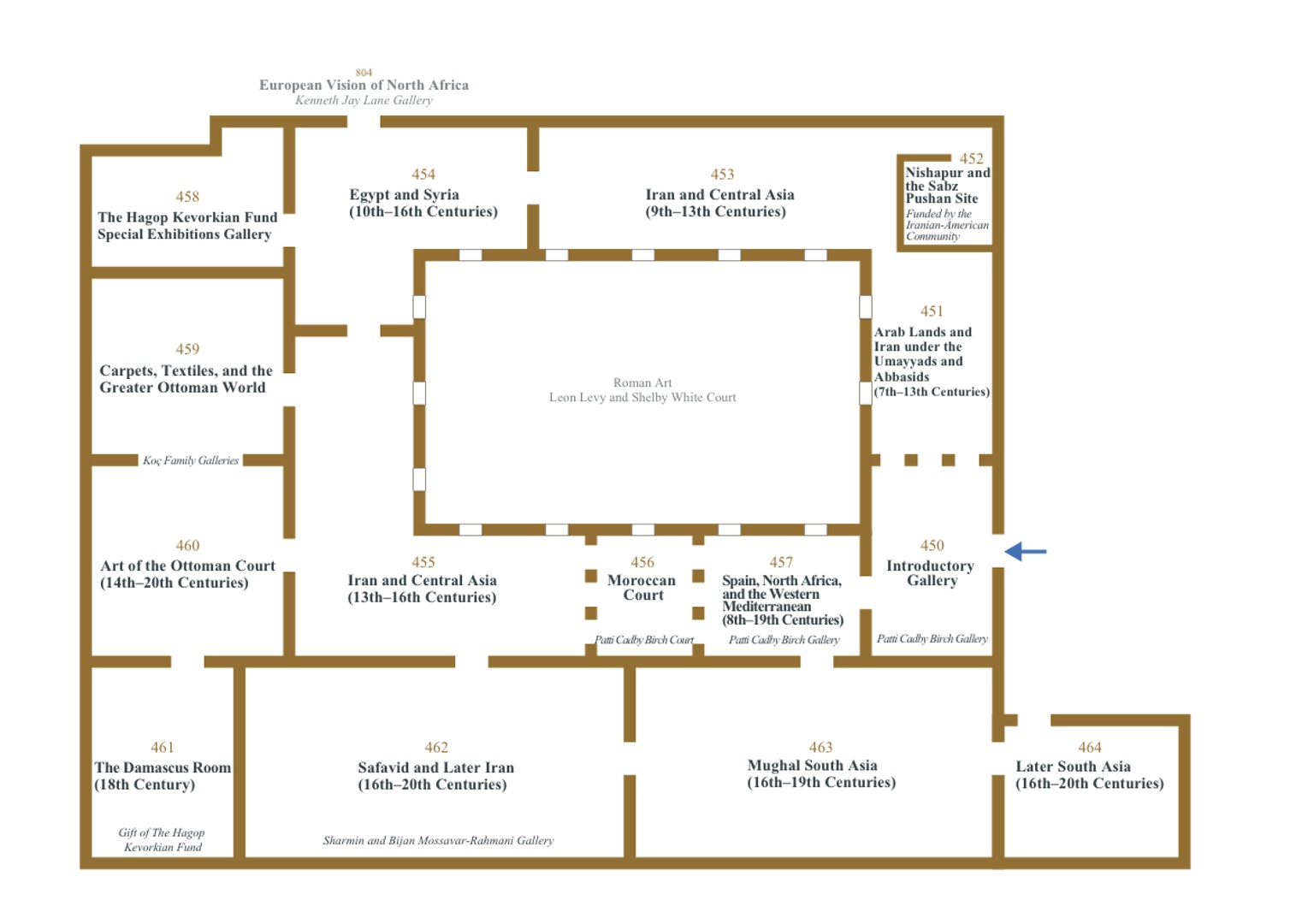

As one can ascertain from the new floor plan, the entire fifteen galleries revolve around one central gallery—that of Roman art. When the Islamic art galleries were closed in 2003 to make room for the Greek and Roman department, the museum was criticized for this move, as it was so close to the events of September 11th, 2001. It was perceived that the Met, a significant institution in the heart of New York City, was annihilating Islam at a very sensitive time.

[Scanned image of floor plan for the renovated galleries]

[Scanned image of floor plan for the renovated galleries]

After unveiling the galleries in late 2011, Greek and Roman art became an architectural nucleus, and although visitors do not see any part of this central gallery, as it is actually located on a lower level, when looking at the floor plan, it appears that they are revolving around it, like Muslims revolve around the Kaaba during pilgrimage in Mecca. There are modern mashrabiyya windows facing the central Roman court, although one might not notice if standing at a distance. The fact that visitors are not aware that they are indeed orbiting around it strengthens a certain Eurocentric experiment. Visitors thus become part of a cultural positioning that is dictated by the museum, whether they are conscious of it or not.

Furthermore, today, the gallery dedicated to Egyptian and Syrian art of the 10th-16th centuries leads to a display room dedicated to the “European Vision of North Africa”, outside those of the ALTICALSA galleries. This room presents artworks by Orientalist painters such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, Adrien Dauzats, Horace Vernet, Théodore Chassériau, Charles-Théodore Frère, Charles Bargue, among others.

In Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ettinghausen discussed the Orientalist collection:

We find a sizable number of paintings of Near Eastern subjects, often done after sketches made during travels in that part of the world. […] Their realism gives these genre scenes or views an ethnographic relevance, as much of this traditional aspect of the Near East has disappeared. […] There seems altogether little doubt that the paintings with such a Near Eastern orientation helped to create an interest in the civilization that had produced these romantic scenes and vistas. [5]

This book was published in 1972, six years before Said’s Orientalism. Although this notion was not as eminent as it is today, Ettinghausen’s viewpoint is exactly what Said denounces. The “realism” of those paintings that fascinated people in the West has been criticized over the course of the last decades for the outsider interpretations that served as a justification for imperial and colonial ambitions. The fact that a gallery dedicated to Orientalism is juxtaposed to the galleries dedicated to Islamic art is questionable. Indeed, the history of colonialism is a genuine part of the history of many Arab and Islamic countries, and evidently the choice made by the curators is commonsensical. Nevertheless, the gallery does not set forth any kind of written explanation or context to help visitors understand the relationship between the Islamic art collection and Orientalist paintings. The curators are therefore relying on visitors to understand this relationship on their own, leaving much space for misunderstandings and misrepresentations.

All the same, to help direct visitors, audio guides usually provide outstanding insight to exhibitions. The first commentary in this case is given by Thomas Campbell, Director of the Met, who introduces himself as “Tom Campbell”, presenting the collection as the “finest of its kind and widest in scope in museums anywhere”. The tone is informal and the director seems almost accessible to the general public. The second account is given by Sheila Canby, who explains that Islamic art was produced on lands expanding from Spain to India, from the 7th to the 19th century, and briefly mentions the characteristics of Islamic art.

The majority of individuals giving the commentaries after Campbell and Canby are all individuals with a thick accent; the choice of speakers is questionable. Although it is true that many individuals from the areas represented in the galleries do have certain accents when speaking English, it is also true that many do not. By exclusively using speakers with accents, the museum emphasizes how different those worlds, and therefore their people, are. One might argue that this accentuates the Orientalist approach that the museum is taking, that all people from the lands and areas represented speak in a different manner relative to the average Western individual (in this case, the average North American).

An aspect of the coinciding educational program that is presented by the department is the lectures and symposia that are offered free with museum admission. An example of these was a panel discussion entitled “Women and the Muslim World: Patrons, Artists, Muses, and Instigators” that was presented on November 18th, 2011. Supported by the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art and moderated by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of Passion for Islam, Caryle Murphy, the panel included Sabiha Al Khemir, Laila Essaydi, Samina Qureshi and Princess Firyal of Jordan. Prior to discussing the content of the conversation, one can notice that the title of this discussion is essentially Orientalist in nature. Presumably, the department wanted to confirm that women in the Muslim world are not oppressed, as they are commonly portrayed; yet the fact that this was done so distinctly actually hardens such stereotypes. Murphy started out the discussion by saying that Islam was a reformist religion. She emphasized the fact that it was a modern religion and gave the example of the Prophet Muhammad, who said that women are “the twin hearts of men”. Murphy elaborated, “We can say that Prophet Muhammad was the first feminist”.

The panel’s opinion of the new galleries was generally positive. Al Khemir emphasized that the galleries are a platform for dialogue between the East and the West, but also “within ourselves”. Qureshi admitted that after September 11th, there was a need to communicate with the rest of the world the plurality of Arabs and Muslims. Finally, Princess Firyal claimed that she was pleased with the designation of “Arab Lands” in the naming of the galleries, as now Islamic art is identified with the lands it was created in. Lalla Essaydi noted that the juxtaposition of the Islamic galleries with the Orientalist galleries was disconcerting. As an artist and a feminist, Essaydi often uses images from Western, Orientalist art, a method she uses to question Orientalist methodology while encouraging viewers to resist stereotypes. Essaydi believes Orientalism still carries on today; for the artist, what is alarming is not only the Western gaze, but how Arabs and Muslims internalize this gaze.

Along with lectures, the museum sought to promote the galleries in magazines and newspapers alike. To attract more visitors, these promotions did not only appear in art-related media, but also in mass media publications, such as Time Magazine and Vogue. Perceptibly, the museum aims to appeal to a wider audience and intends to make the collection more accessible and easily understood. As part of this extensive marketing campaign, Vogue dedicated four pages of its February 2012 issue to curator Navina Najat Haidar and the new galleries. The writer accounts for the public visiting the galleries with the kind of description that functions to accost East and West, “[…] people of all ages, speaking various languages, some of them wearing headscarves and others backward-facing baseball caps”. The headscarf is one of the obvious ways one can recognize a Muslim woman; it is also a polemic matter, while the baseball cap is a clichéd way of describing the average American. Likewise, the article makes reference to the curator’s personal and religious background:

Navina, an elegantly graceful, dark-haired woman in her mid-40s, has a many-cultured background that makes her especially well suited to the sensitivities of her chosen field. “I was born in London, but I`m from India. […] My father is Muslim, and my mother is Hindu.” [6]

That such information is revealed throughout the article demonstrates an effort to make the department, and the people behind it, more authentic and personable in order to gain credibility. Moreover, this paragraph may well indicate that someone with a less diverse or distinct background is not suited for this field and the “sensitivities” that come with it, yet Haidar’s explanation of her background is dubious. Does the fact that her father is Muslim and her mother is Hindu automatically make her the perfect candidate for her position? Of course, one cannot forget that this article was published in Vogue, and certainly the museum is trying to open itself to uninformed and new audiences. While it can be argued that such cursory investigations do not meet the standards the Met has set for itself or for its new galleries, it clearly meets Vogue’s standards. Nevertheless, there is a popularization of Islamic art, which becomes palatable and fashionable; trying to understand Islamic art is the newest trend, but falls short of addressing the realities at hand.

[Hanging (ca. 1640-50) from Deccan, India. Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

[Hanging (ca. 1640-50) from Deccan, India. Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

According to the museum, the makeover of the Department of Islamic Art was done in a way to show a side of Islam that is unknown or insufficiently known—one that stresses the culture and the arts that are associated with this religion—to give a better understanding of Islamic civilizations. Although there is no doubt that the New York City institution has one of the largest and most extensive collections of Islamic art in the world, the display, explanation and commentaries of those objects, as well as the rationale behind it, can indisputably be questioned. In a way, the renovated galleries attempt to rewrite history and distance this art from the religion it is inevitably tied to. The history of colonialism is a biased history, and this exhibition only replaces it with an equally subjective one. Enormous and powerful institutions, such as the Met, rearticulate and reinforce certain issues, whether cultural, social, or political, through their exhibitions. By questioning the renewed interest in Islamic art, one should be able to discern if this sort of exhibition is becoming a valid way the West can gaze at the Other.

[1] Hoving, Thomas. Making the Mummies Dance: Inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1993). Simon & Shuster: New York.

[2]"Renovated Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia Now Open." Review. Web log post. New Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Web Jan 17, 2012.

[3] Welch, Stuart Cary. The Islamic World (1987). Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York.

[4] Diman, Maurice Sven. A Handbook of Mohammedan Decrotive Arts (1930). Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York

[5] Ettinghausen, Richard. Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1972). Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York.

[6] Kazanjian, Dodie. "The Magic Touch" Vogue, Feb, 2012.